Abstract

On May 15, 2023, Envision Healthcare Corp. (“Envision”) announced that it and several of its subsidiaries had filed voluntary petitions for reorganization under Chapter 11 of the United States Bankruptcy Code. This news prompted a swift reaction within the healthcare industry as Envision reports itself as “one of the nation’s leading medical groups, delivering physician and advanced practice provider care in settings where patients have the most acute and life-changing needs – emergency departments, surgical suites, intensive care units and birthing suites – through Envision Physician Services.”[1] Because of its large role in the successful functioning of emergency departments (“EDs”) across the country, Envision is often regarded as crucial to the functioning of the country’s healthcare system. Because of this role, Envision’s petition for bankruptcy has caused widespread speculation as to the direction of emergency care for patients, particularly as the industry’s provider workforce had already been strained in recent years due to a myriad of issues.

In this article, we delve into the multifaceted obstacles that EDs encounter daily, discuss recent events and trends that are materially affecting emergency care delivery, examine the financial and regulatory repercussions associated with these issues, explore the recent collapse of provider staffing firms, consider key elements of provider staffing and compensation, and discuss the urgent need for viable solutions into the future. Understanding these challenges will remain crucial as we work toward bolstering ED coverage to ensure the well-being of both patients and providers.

Background

Overview of Emergency Care

Contrasted with other medical specialties, emergency patients can present with a wide array of acute symptoms and can do so at any time, at any age, and with any co-morbidity. Because the nature of emergency medicine ensures a constant state of unpredictability, the delivery of care in this setting remains a formidable challenge. Thus, while hospital EDs are crucial for healthcare delivery and represent a lifeline for patients, management of this care is oftentimes characterized as a battleground.

As has been argued by industry experts, an “effective emergency care system serves three major functions: (i) it serves as a primary point of entry into the healthcare system for all patients with symptomatic conditions, (ii) it provides time sensitive management of acute exacerbations of chronic disease, and (iii) it serves as a crucial safety net for patients without other linkages to healthcare.”[2] The passage of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (“EMTALA”) in 1986 further clarified this role as it requires hospital EDs that accept payments from Medicare to provide care to any patient seeking treatment for a medical condition, regardless of citizenship, legal status, or ability to pay.[3] This dynamic function underscores the importance of maintaining robust staffing and optimal functioning within EDs, thereby safeguarding the accessibility and quality of healthcare services.

Despite its importance, factors such as the rapid influx of patients, the acuity of critical cases, and continuously changing dynamics ensure constant pressure on healthcare facilities and create a daunting landscape that necessitates a resilient and well-prepared staff. Therefore, even with the challenges of emergency care, ED provider staffing serves as a critical function to the overall delivery of healthcare nationwide.

Trends Affecting ED Care Delivery

Despite the importance of ED provider staffing, several factors have contributed to its uncertainty and erosion in recent years. While Covid-19 undoubtedly presented a seemingly insurmountable obstacle to healthcare delivery, several issues pertinent to ED care had been looming prior to the impact of the pandemic. Specifically, healthcare providers were already grappling with issues such as an aging population, increased patient obesity, a rise in co-morbidities, physician shortages, and provider burnout. The aggregate effect of these trends seemed to point to an inevitable intersection of increased demand for healthcare services with a simultaneous decrease in provider availability.

While this crossroad has been a cause for concern for years, the Covid-19 pandemic only further exacerbated these developments. The potential repercussions of a void in patient care are alarming in any instance, but particularly given the country’s rise in co-morbidities and the elderly patient population.[4] Ensuring the delivery of timely, high-quality care is becoming a more urgent concern, especially given complications intensified by the pandemic and the collapse of notable provider staffing firms.

While EDs scramble to formulate solutions ensuring patient access to necessary care, they have continued to experience overcrowding, a trend only worsened by Covid-19. ED crowding, a critical issue plaguing organizations worldwide, is characterized by an overwhelming demand for emergency services that surpasses the available resources for patient care in the ED, hospital, or both.[5] This relentless pressure on EDs has far-reaching consequences, including adverse effects on morbidity, mortality, medical error rates, staff burnout, and excessive costs. Moreover, the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic has only exacerbated the challenges associated with crowding, leading to a substantial increase in overall ED patient lengths of stay (“LOS”).[6]

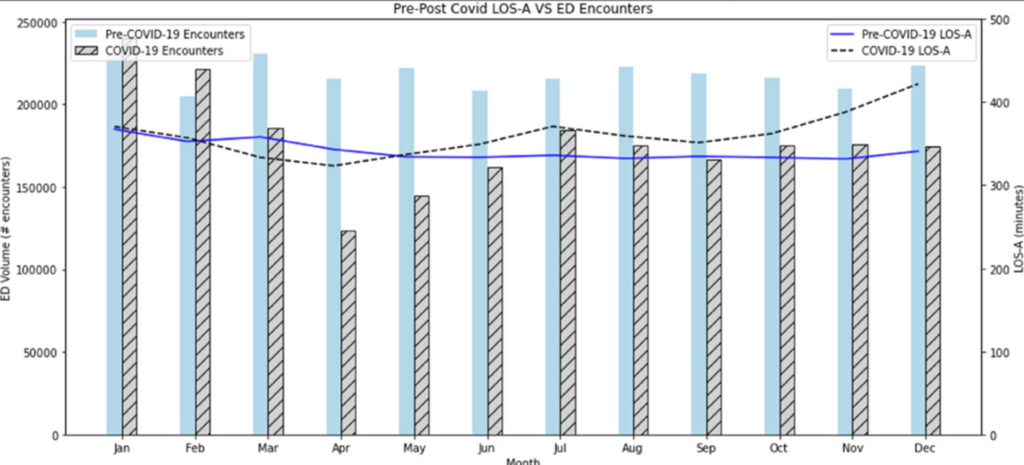

According to analysis by the Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open (“JACEP Open”), ED LOS was “significantly higher during the Covid-19 period compared to the pre-Covid-19 period”.[7] These indicators are alarming given the fact that increased LOS leads to further ED overcrowding. Because EDs represent the front line of the healthcare system, this strain on hospital resources inevitably trickles down to patient experience and outcomes. The following table, compiled as part of the JACEP Open assessment, illustrates the distinction between LOS prior to and during the pandemic.[8]

Despite the impact of the pandemic, alarming statistics revealed that even before the Covid-19 outbreak, over 90% of U.S. EDs were frequently operating under significant stress, pushing them to their breaking point.[9] As the primary entry point into the healthcare system for most SARS-CoV-2-infected patients, EDs faced unparalleled strain during the pandemic, exposing their vulnerabilities and limitations in responding effectively and safely to such crises within severely crowded environments.[10] The combination of ED crowding and the exigencies of the Covid-19 virus has shed a glaring light on the urgent need for sustainable solutions to safeguard the efficiency and effectiveness of emergency care delivery.

In an attempt to effectuate such care and expand patient access to emergency providers, many organizations are reviewing their provider staffing model to better utilize advanced practice clinicians (“APCs”) including physician assistants and nurse practitioners. While ED staffing is a pivotal factor in delivering efficient and high-quality patient care, it remains a constant challenge for healthcare institutions to maintain optimal nurse-to-patient ratios. In recent years, nursing organizations, labor unions, and policymakers have been pushing for mandated nurse-to-patient ratios in EDs, advocating for a range from 1:4 for general ED patients to 1:1 for trauma cases.[11]

In spite of the importance of ED providers, the emergence of Covid-19 has intensified the strain on ED staffing, compelling a significant portion of health care workers to contemplate leaving the profession due to the overwhelming stress and demands of the crisis. A troubling Kaiser Family Foundation/Washington Post poll revealed that approximately three in ten health care workers considered abandoning their careers, while about six in ten reported a detrimental impact on their mental health due to pandemic-related stress. The relentless workforce challenges posed by the pandemic have also come at a staggering financial cost, with hospitals collectively incurring $24 billion in staffing shortages and an additional $3 billion in acquiring personal protective equipment (“PPE”) to safeguard their staff.[12] The pressing need to address ED staffing shortages and support the well-being of healthcare professionals has become more apparent than ever, underscoring the urgency for strategic interventions to ensure sustainable and resilient emergency care systems.

Financial Impact of ED Staffing Challenges

The ramifications of the ED staffing crisis extend far beyond the realm of patient care, significantly affecting the financial health of healthcare institutions. The scarcity of qualified medical personnel has led to a surge in wages as hospitals endeavor to attract and retain skilled staff, imposing a substantial burden on their resources.

According to Fitch Ratings, labor expenses (encompassing salaries and benefits) constitute the largest expense category for hospitals, accounting for over 50% of their total expenditures. Between February 2020 and August 2021, average hourly wages for hospital employees have skyrocketed by 8.5%, and there are no indications of this inflationary trend abating anytime soon. The escalating costs are set to deal a severe blow to hospital margins in the coming year, as projected by credit rating agency Moody’s, owing to a combination of wage inflation, the mounting expenses incurred in hiring expensive contract provider staffing firms, and the implementation of additional worker benefits to retain employees.[13]

As the financial strain continues to escalate, healthcare institutions find themselves at a crossroads, navigating the delicate balance between sustaining operational viability and ensuring the delivery of quality patient care amidst the relentless challenges of ED staffing. The collapse of ED staffing firms is causing further concern for provider availability, a fact which underscores the importance of strategically planning for provider retention as well as leveraging the work of APCs to alleviate burdens placed on ED physicians.

Case Study: Envision Bankruptcy

In the midst of the already stressed ED environment, Envision jolted the industry with its recent decision to seek Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Given its reputation as one of the nation’s prominent healthcare staffing firms, this development has triggered concerns among industry observers, raising questions about the financial stability of other third-party staffing agencies. On the heels of the Envision announcement, American Physician Partners (“APP”), another medical staffing company serving numerous hospitals across 18 states, announced that it plans to wind down its operations and transition its hospital contracts. APP had grown rapidly since it was founded in 2015, with its revenue jumping 154.2% from 2018 to 2021 – a fact which made it one of Nashville’s ten largest privately owned businesses.[14] Citing ongoing financial challenges amongst its struggle to repay its overdue loans, the company’s closure came swiftly, with the transition starting as of July 31, 2023.[15] Yet another example following Envision’s announcement, this trend is troubling for a healthcare system already struggling to staff EDs in an effort to meet increased patient demand.

Given that both companies folded in rapid succession citing financial troubles, the underlying business model could be a significant part of the cause. Oftentimes, the structure of healthcare staffing companies entails carrying significant debt and maintaining relatively lower cash reserves. This mode of business can expose these firms to greater risk, particularly when dealing with transient providers, leading to fluctuations in cash flow. For Envision, these challenges manifested in a series of financial setbacks, culminating in the bankruptcy filing.

One key factor which reportedly contributed to Envision’s financial troubles was the enactment of the No Surprises Act (“NSA”). Prior to the NSA, patients seeking treatment at in-network healthcare facilities (including EDs) could be billed at out-of-network rates if the agency through which the facility staffed its services was not in-network. The NSA aimed to curb such unexpected out-of-network bills, providing consumer protection against surprise medical expenses.

However, Envision contended that the NSA’s implementation deviated from its intended purpose, allowing health insurers to delay, reduce, or deny payments. According to Envision, these factors led to substantial losses for the company. Alleged underpayments and prolonged waiting periods for reimbursements reportedly amounted to hundreds of millions of dollars in financial losses for Envision, contributing significantly to the dire financial situation that culminated in the bankruptcy filing.[16]

Similarly, the closure of APP adds to the list of provider staffing entities grappling with financial challenges in the wake of the NSA taking effect on January 1, 2022. While the goal of the legislation aimed at curbing surprise medical bills for emergency services and out-of-network care, these organizations report that it has resulted in significant financial strain.[17] The distress faced by APP, coupled with similar instances such as Envision’s bankruptcy filing, highlights the substantial impact of regulatory changes on the financial stability of healthcare staffing firms. The ripple effect of this type of financial turmoil has direct implications for ED staff burnout, as the uncertainty surrounding the viability of staffing companies may heighten the stress and apprehension experienced by frontline healthcare professionals.

The high-profile Envision bankruptcy – as well as the rapid closure of APP – serves as a cautionary tale, prompting a closer examination as to the financial vulnerabilities of healthcare staffing firms and raising concerns about the broader implications for the industry as it grapples with evolving regulatory landscapes and financial challenges. In the event continued workforce strain amongst ED providers has a material impact on patient care, the effect may lead to problems with the overall delivery of healthcare. Thus, the implications of Covid-19 and the Envision bankruptcy only further exacerbate an already existing set of troubling circumstances.

Comments from a Valuation Perspective

As the landscape of ED care evolves, so too will the considerations around provider compensation. As previously discussed, a certain amount of uncertainty exists regarding wages in the wake of the pandemic. Particularly as issues such as provider shortages, burnout, and increased patient demand continue to persist, healthcare organizations will be fervently working to ensure its facilities are staffed with adequate providers to achieve necessary patient access.

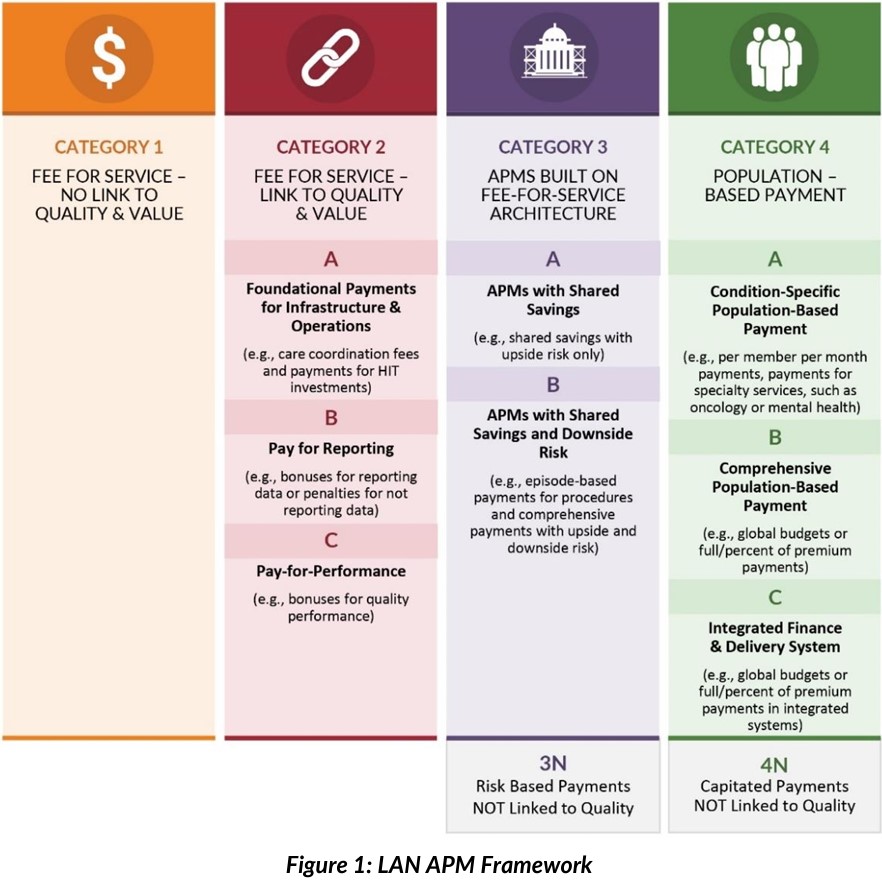

While the need for providers is anticipated to persist on an ongoing basis, hospitals and health systems must nonetheless adhere to regulatory requirements, one of which is the need to ensure provider compensation (i.e., in certain circumstances) is consistent with fair market value (“FMV”). While the determination of FMV does not require review by an outside party, many organizations are managing their risk exposure by relying on legal counsel and valuation professionals to construct and review agreements, including their financial terms.

From a valuator’s standpoint, determining FMV compensation for physicians and APCs involves a complex process that requires a comprehensive analysis of various factors. Several statutory, regulatory and administrative definitions exist related to the concept of FMV. Given said definitions, valuators will generally gather a reasonable knowledge of available, relevant factors associated with a subject arrangement. Based on this knowledge, they then derive an estimate of value (i) as if there was no compulsion to buy or sell, and (ii) without taking into consideration the business either party could generate for the other. In other words, FMV refers to the price at which two independent and knowledgeable parties would agree to a transaction, reflecting the true value of the services rendered.

When it comes to compensating healthcare providers, valuations should account for numerous factors, including the specific qualifications and experience of providers, regional market conditions, patient volume, specialty demand, and the complexity of the healthcare facility’s case mix. In addition to factors specific to each individual subject arrangement, key considerations generally taken into account by valuators and legal counsel include:

- Ensuring that the compensation arrangements adhere to strict regulatory guidelines (e.g., state-specific requirements in addition to the Stark Law, the Anti-Kickback Statute, and rules for 501(c)(3) organizations) to avoid potential legal ramifications;

- Considering any specific requirements or restrictions related to compensation set forth by payors, accreditation bodies, and industry standards; and,

- Accounting for the type of arrangement and any ascertainable quality metrics amid the evolving healthcare landscape in which shifting reimbursement models and changing workforce dynamics are factors.

The valuator’s expertise is pivotal in ensuring that the compensation packages strike a balance between attracting and retaining skilled healthcare professionals while safeguarding the organization’s financial sustainability. With the growing emphasis on healthcare value and cost-effectiveness, valuators will often gauge the competitive nature of the market to ensure that the compensation aligns with comparable rates in the region while complying with FMV standards. A thorough and meticulous valuation process ultimately lays the foundation for equitable and compliant compensation structures that foster a strong and sustainable healthcare workforce.

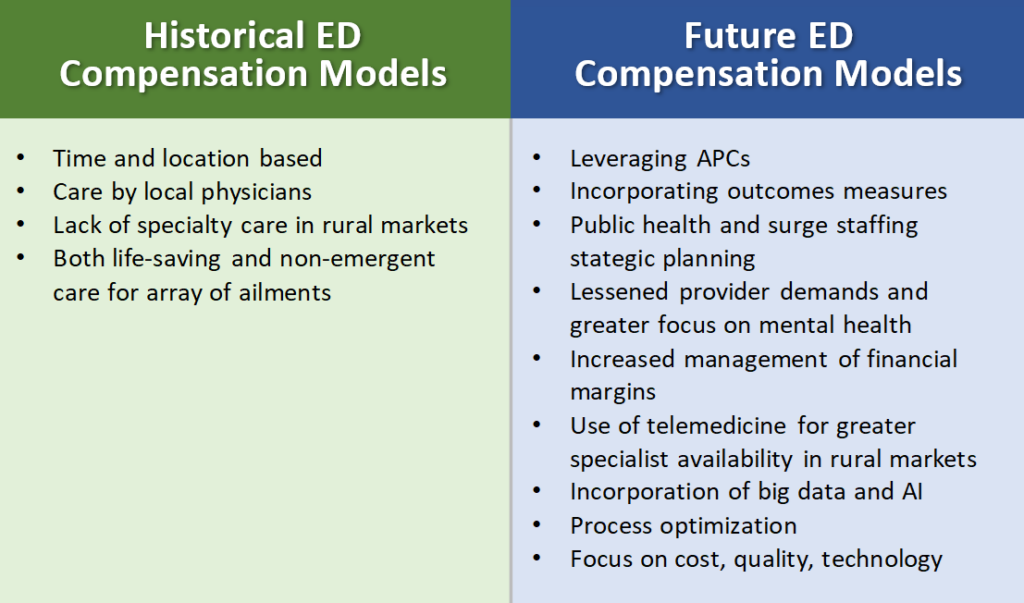

Specific to ED compensation considerations, these provider compensation arrangements have often been historically structured on a “per shift” basis. These shifts were almost exclusively covered by providers in the local market. Because ED physicians and APCs are providing hospital coverage for emergent patient cases, the EDs must be adequately staffed with sufficient providers to ensure access for patient care. In contrast with other specialties in which providers offer services on a scheduled or as needed basis, ED compensation arrangements contemplate provider services in the context of a time-based (i.e., versus volume-based) approach.

That fact notwithstanding, the determination of FMV compensation for ED physicians and APCs presents unique challenges influenced by several factors, including ED crowding and the ongoing impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. EDs, often at the frontline of healthcare crises, experience fluctuating patient volumes and unpredictable demand for services, directly impacting the valuation of provider services. ED crowding, an ever-present concern, can lead to extended patient LOS, increased medical errors, and heightened staff burnout, necessitating careful assessment by the valuator to determine FMV for healthcare professionals. The Covid-19 pandemic further amplified the strain on EDs, as they faced increased patient encounters/LOS, resource shortages, and unprecedented levels of stress on the healthcare workforce.

While ED provider compensation has typically been assessed on a coverage (i.e., shift) basis which often included subsidized professional collections, Covid-19 resulted in many facilities regularly utilizing “surge staffing”. Not uncommon in ED staffing even prior to the pandemic, this type of model was used in combination with existing shift-based arrangements in the event a facility required resources on a basis that was greater than that initially anticipated. While surge staffing existed prior to the pandemic, its use skyrocketed to meet increased demand associated with Covid-19. This type of provider staffing generally involves compensation on an hourly basis to account for the unpredictability of the services required. In the event a surge in patient volume occurs, ED management and/or medical directors can call on additional “surge” staffing by utilizing overtime or externally staffed providers at higher compensation rates.

In addition to flexible staffing models, a further anticipated change in ED staffing includes a greater utilization of APCs to provide patient care. Not only do APCs leverage physician time and provide greater patient access, their compensation and benefits reflect a lower cost than that of physicians. As hospitals continue to grapple with lessened financial margins and increased strain in the wake of the pandemic, a leveraged model using APCs may provide them an option to not only increase the number of providers offering care but also to do so in a less expensive format than a physician-only model (i.e., assuming that the quality of care continues at the same level). As provider expenses continue to comprise the largest item of cost for hospitals, a lessening of these expenses may provide a win-win for both healthcare facilities and for patients.

While the industry continues to transform into its likely future state, provider staffing and compensation models will likewise evolve. Greater use of tools not previously available will undoubtedly be a key consideration. For instance, EDs were historically staffed with local providers, with a less than favorable availability for certain specialists in rural markets. An increase in the use of telemedicine and data in the form of artificial intelligence (“AI”) will almost certainly continue into the future. While the industry remains in a state of change, ED care will undoubtedly make use of new tools, ensuring adaptation within provider compensation models. Outlined in the following table are some of the considerations that may differentiate future ED provider compensation models from those of the past.

These adaptations and challenges underscore the importance of valuing provider services in a manner that considers the dynamic nature of ED operations while maintaining compliance with regulatory guidelines. Additionally, the valuation must account for regional variations in ED volumes, payer mix, and available resources, as these factors can significantly influence the FMV of physician and APC compensation. Ultimately, a comprehensive and nuanced valuation approach is essential to develop equitable compensation structures that support quality care delivery while addressing the complexities introduced by ED crowding, the pandemic’s impact, and other relevant variables.

Implications for the Future

Looking ahead, the challenges surrounding ED coverage present critical implications for the future of healthcare delivery. The persistent issue of ED crowding which is exacerbated by demographic shifts, population growth, and evolving healthcare needs, is likely to continue pressuring medical facilities and professionals. As the world grapples with the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, the healthcare industry should brace itself for potential resurgences or future public health crises, demanding a prepared and resilient workforce.

In addition to provider access amongst increased patient demand, organizations will be tasked with addressing the financial impact of ED staffing challenges to ensure the sustainability of healthcare institutions, even in the face of mounting expenses and reimbursement complexities. Likewise, the valuator’s role will be increasingly crucial in shaping compliant compensation structures for physicians and APCs within ED settings, while also taking into account dynamic factors such as ED crowding, pandemic preparedness, regulatory compliance, and changes in coverage models.

To fortify emergency care, healthcare organizations, policymakers, and industry stakeholders must collaboratively explore innovative staffing models, optimize resource allocation, and invest in technology and telemedicine solutions to enhance efficiency and patient outcomes. By proactively addressing these challenges and implementing sustainable solutions, the future of ED staffing and coverage will be better safeguarded, ensuring that quality care remains accessible, regardless of the uncertainties that lie ahead.

Closing Comments

To conclude, the challenges in ED staffing and coverage represent an evolving and multifaceted landscape that demands immediate attention and sustainable solutions. ED crowding continues to stress resources, which in turn jeopardizes patient outcomes and contributes to escalating healthcare costs. The unprecedented impact of the Covid-19 pandemic further highlighted the vulnerabilities in emergency care, amplifying both workforce and financial burdens. As if on cue, Envision’s bankruptcy – followed shortly thereafter by APP’s collapse – serves as a stark reminder of the risks faced by healthcare staffing firms and the need for prudent financial management.

A key element in this financial management involves provider staffing models and associated compensation. Hospital administrators, valuation professionals, and counsel play a pivotal role in determining arrangement structure and ascertaining FMV compensation for emergency physicians and APCs alike. While valuators and hospital management must navigate the complexities of ED operations and regulatory compliance, ensuring compliant compensation is a large part in the risk management efforts of healthcare organizations.

As the healthcare industry charts a course toward the future, strategic planning and collaborative efforts are essential to address these challenges. By embracing innovative staffing models, leveraging technology, and prioritizing patient-centered care, healthcare institutions can fortify their emergency care systems, ensuring that both patients and healthcare professionals receive the support they require. A resilient and well-prepared ED workforce is fundamental to meeting the diverse and unpredictable demands of emergency medicine, safeguarding the well-being of communities and upholding a standard of excellence in healthcare delivery.

[1] As reported at https://www.envisionhealth.com/news/2023/envision-healthcare-reaches-restructuring-agreement.

[2] As reported at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211419X20300707; citing, L.C. Carlson, T. Reynolds, L.A. Wallis, E.C. Hynes, Reconceptualizing the role of emergency care in the context of global healthcare delivery, Health Policy Plan, 34 (2019), pp. 78-82.

[3] 42 U.S. Code § 1395dd.

[4] Péterfi, A., Mészáros, Á., Szarvas, Z., Pénzes, M., Fekete, M., Fehér, Á., Lehoczki, A., Csípő, T., & Fazekas-Pongor, V. (2022). Comorbidities and increased mortality of covid-19 among the elderly: A systematic review. Physiology International, 109(2), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1556/2060.2022.00206

[5] American College of Emergency Physicians Policy Statement.

[6] Lucero A, Sokol K, Hyun J, et al. Worsening of emergency department length of stay during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open 2021;2:e12489; as reported at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/

10.1002/emp2.12489.

[7] As reported in the Wiley Online Library at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/emp2.12489#.

[8] Id.

[9] Institute of Medicine. Hospital-based emergency care: At the breaking point. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2007

[10] As reported at https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.21.0217

[11] As reported at https://journals.lww.com/nursingmanagement/Fulltext/2005/09000/Nursing_workforce_issues_

and_trends_affecting.11.aspx.

[12] As reported at https://www.aha.org/fact-sheets/2021-11-01-data-brief-health-care-workforce-challenges-threaten-hospitals-ability-care.

[13] Id.

[14] As reported at https://www.bizjournals.com/nashville/news/2023/07/18/american-physician-partners-to-close.html.

[15] As reported at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-07-17/american-physician-partners-to-close-doors-after-cash-squeeze#xj4y7vzkg.

[16] As reported at https://www.modernhealthcare.com/finance/envision-healthcare-bankruptcy-staffing-no-surprises-act-unitedhealth-lawsuit.

[17] As reported at https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-physician-relationships/american-physician-partners-to-close.html