Introduction & Background

Following the enactment of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) in March 2010, the healthcare industry has experienced a major shift in its reimbursement and payment structure. While the United States healthcare system had historically operated under a fee-for-service (FFS) model, the PPACA initiated a notable shift to value-based care (VBC). Under the traditional FFS model, providers are paid separately for each medical service. Because of this structure, the FFS model has been characterized as a ‘volume-based’ payment model, under which healthcare expenditures notably increased. Many argue that this outcome was inevitable given that the FFS model incentivizes physicians to provide more treatments. In this way, industry experts characterize the FFS model as dependent on the quantity – rather than the quality – of care.

On the other hand, a VBC model delivers healthcare through a structure that pays providers based on the quality of services rendered. These providers – whether physicians, hospitals, labs, advanced practice providers (APPs), or other – are therefore reimbursed based on the health outcomes of their patients rather than on the volume of services rendered. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), VBC can be described as “designing care so that it focuses on quality, provider performance and the patient experience.”[1] Several different models have been developed to deliver VBC, including accountable care organizations (ACOs), alternative payment models (APMs), care coordination, and integrated care, among others. As this area of healthcare delivery continues to evolve, additional models continue to develop – one of which is known as the AHEAD model.

The AHEAD model – which stands for All-Payer Health Equity Approaches and Development (AHEAD) – is a voluntary, state total cost of care (TCOC) model. According to CMS, TCOC is defined as “the process of holding participating states accountable for quality and population health outcomes, while constraining costs of healthcare services delivered in a state or specified sub-state region.”[2] As applied by CMS, this process occurs across all payers, including Medicare, Medicaid, and private health insurers. Put simply, TCOC represents total spending on healthcare. The AHEAD Model aims to reduce these healthcare costs while also improving health outcomes. Outlined in the following sections are notable components of the AHEAD Model, key considerations, and how VBC experts can help.

Model Overview

The AHEAD Model, which is anticipated to operate from 2024 through 2034, provides an opportunity for states to take accountability for population health, health equity improvements, and FFS TCOC. Under the Model – which expects to improve health outcomes and quality – states will collaborate with hospital and primary care providers (PCPs) to “redesign care delivery to focus on keeping people healthy and out of the hospital.”[3]

According to CMS, its stated objective with the AHEAD Model is to:

- Collaborate with states to curb healthcare cost growth;

- Improve population health; and,

- Advance health equity by reducing disparity in health outcomes.[4]

In accordance with this objective, CMS will support states participating in the AHEAD Model through:

- Increasing investment in primary care;

- Providing stability for hospitals; and,

- Supporting beneficiary connection to community resources.[5]

Under the AHEAD Model’s TCOC approach, participating states will assume responsibility for managing healthcare quality and cost across payers. CMS indicates that the primary goal of the AHEAD Model is “improving healthcare outcomes and health equity for all residents within a participating state or region.”[6]

While it builds on the work of existing state-based models, CMS reports that the AHEAD model is different because it will implement the AHEAD Model concurrently across multiple states. CMS anticipates that the AHEAD Model will enable participating states to increase investment in primary care while also constraining TCOC growth. Overall, CMS wishes for the AHEAD Model to encourage a “state-level, multi-sector approach to care, advancing health equity and thereby improving population health outcomes, and coordinating resources to address underlying factors that contribute to disparities in health outcomes in underserved communities.”[7] In effect, the AHEAD Model will test state accountability for controlling overall growth in healthcare expenditures – while increasing investment in primary care and improving population health outcomes within a participating state or state region.

Application Process

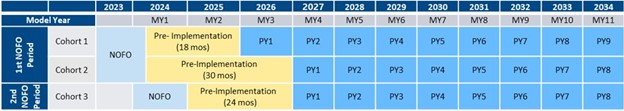

States that wish to participate in the AHEAD Model can take part in the application process which begins in Spring 2024. Applicants must apply to the Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) which was released in late 2023. According to CMS, it expects to award cooperative agreements to up to eight states across two application periods. For those states applying to participate in the AHEAD Model, they must select one of three cohorts depending on their level of readiness for implementation. These three cohorts and the associated key considerations for each are as follows:

- Cohort 1:

- Pre-Implementation Period – 18 months, tentatively July 2024 – December 2025

- Readiness – State is ready to apply and implement the AHEAD Model as soon as possible

- Performance Years – Will tentatively begin January 2026, with a total of nine performance years

- Cohort 2:

- Pre-Implementation Period – 30 months, tentatively July 2024 – December 2026

- Readiness – State is ready to apply to the AHEAD Model but requires additional time to prepare for implementation (e.g., developing Medicaid components, recruiting healthcare providers for participation, developing data infrastructure, etc.)

- Performance Years – Will tentatively begin January 2027, with a total of eight performance years

- Cohort 3:

- Pre-Implementation Period – 24 months, tentatively January 2025 – December 2026

- Readiness – State needs additional time to apply

- Performance Years – Will tentatively begin January 2027, with a total of eight performance years[8]

While the AHEAD Model plans to function for 11 years (i.e., 2024 through 2034), CMS will provide funding to chosen states for up to six years in support of participation. Specifically, CMS plan to award each participating state a maximum of $12 million with performance periods beginning in either January 2026 or January 2027, depending on cohort. According to CMS, it is testing the AHEAD Model over a longer period (to end in December 2034) to allow appropriate time for primary care investment and enhanced care coordination with a goal of resultant improved health with less spending.

Requirements & Participation Targets

The AHEAD Model’s general objective is to improve health outcomes across multiple states. Key strategies to achieve this objective include:

- An All-Payer Approach;

- Medicaid Alignment;

- Behavioral Health Integration;

- Equity Integrated Across the Model; and,

- Accelerating Existing State Innovations.[9]

The financial support provided by CMS for the selected states will be provided via Cooperative Agreement (CoAg) Funding. This funding, along with primary care AHEAD initiatives and hospital global budgets (HGBs – wherein hospitals receive a pre-determined, fixed annual budget), comprise the key components of the AHEAD Model. In order to be eligible for AHEAD Model participation, applicants must have “at least 10,000 resident beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B residing in the applicant state or sub-state region.”[10] Eligible AHEAD Model applicants must have the authority to accept the CoAg Funding (e.g., state Medicaid agency, state public health agency, state insurance agency). CoAg awards differ from grants in that CoAg funding has a substantial degree of federal involvement in carrying out the funded activity (i.e., as opposed to the type of administrative requirements imposed). With regard to the AHEAD Model, the NOFO stated specific parameters around the manner in which the CoAg funding can be used. The funding is generally intended to support model planning and implementation activities, including:

- Recruiting primary care providers and hospitals to participate in the model;

- Setting statewide TCOC cost growth targets and primary care investment targets;

- Building behavioral health infrastructure and capacity;

- Supporting Medicaid and commercial payer alignment;

- Hiring new staff to support the model;

- Investing in new technology;

- Supporting demographic data collection; and,

- Developing Medicaid HGB methodology.[11]

While the above list is not an exhaustive description of CoAg fund usage, it provides examples that aim to promote appropriate planning and implementation of the AHEAD Model. If successful, applicants will receive a Notice of Award (NoA) which authorizes the CoAg.

For those states selected, operational milestones that must be met prior to certain performance years (PY) as part of the CoAg include:

- State Agreement Negotiation and Signature by State Leadership and CMS

- Execution of State Agreement – 6 months prior to PY1

- Creation and Implementation of All-Payer TCOC and Primary Care Investment Targets

- Creation of Targets – 90 days before PY1

- Finalization of Targets – 90 days before PY2

- Successful Recruitment of Hospitals to Participate in Medicare FFS HGBs

- Hospitals Agree to Participate – 10% of Medicare FFS Net Patient Revenue (“NPR”) Would be Under Medicare FFS HGBs by PY1

- Hospitals Agree to Participate – 30% of Medicare FFS NPR in an HGB for PY3 for each subsequent PY

- Implementation of Medicaid Primary Care APM

- Implementation of Medicaid Primary Care APM with Participation from Primary Care Practices by the beginning of PY1

- Implementation of Medicaid HGBs

- Implementation of Medicaid HGB by the end of PY1

- Commercial Payer Alignment with HGBs

- At Least One Commercial Payer Participating in HGBs by the start of PY2

While these milestones will be included in the CoAg, precise dates will be dependent on the NOFO for which a state is applying.

Additional Detail & Notable Issues

While the AHEAD Model and its requirements are numerous, several key considerations are worth noting. As such, we have outlined below additional detail and notable topics to provide as much information as possible.[12] While additional relevant information on each of the below subjects is available, outlined below are an overview of each.

- Implementation Context – the AHEAD Model can be implemented both for managed care and FFS Medicaid populations.

- Data Collection and Sharing – participating states must collect and report statewide quality, health equity, and all-payor TCOC and primary care investment performance data.

- Establishment of Quality Measures – participating states will select a set of quality and population health measures from a menu of options provided by CMS. States will set specific targets for each selected measure (subject to CMS approval).

- Individual Beneficiary Experience – at the provider level, hospitals will use the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey, which assesses an individual’s care experience.

- State Performance Assessment – CMS will assess state performance on generated savings relative to the state’s projected TCOC growth absent the model. Each participating state will be responsible for certain growth and investment targets.

- Health Equity – participating hospitals and primary care practices will be required to collect demographic and social needs data which will be used to identify health disparities and measure progress toward improvement. HGBs will be adjusted based on improvements in equity of health outcomes and quality of care.

- Behavioral Health – participating primary care practices will be required to engage in behavioral health integration activities as a component of Primary Care AHEAD care transformation requirements.

- State Funding Sustainability – interested states should develop a detailed sustainability plan; and, CMS recommends that states consider strategies to sustain funding and AHEAD Model activities throughout the implementation period.

- Simultaneous Participation – CMS models and programs that can concurrently operate within an AHEAD state or sub-state region (which certain conditions and restrictions) include:

- ACO Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (ACO REACH)

- Cell and Gene Therapy (CGT) Access

- Guiding an Improved Demetia Experience (GUIDE)

- Innovation in Behavioral Health (IBH)

- Medicare Shared Savings Program

- Primary Care First

Models that cannot concurrently operate within overlapping geographic regions include:

- Making Care Primary (i.e., MCP)

- Transforming Maternal Health (TMaH)

- Hospital and Health System Participation – during the NOFO period, hospitals and health systems can consult with applicable state agencies to inform of their intent to participate in the AHEAD Model. During the AHEAD Model, they can participate in HGBs as a mechanism to improve care delivery and population health.

- Benefits for Participating Hospitals – Participating hospitals will benefit from (i) stable funding through HGBs, (ii) technical assistance and learning activities, (iii) use of benefit enhancements to support care redesign efforts, and (iv) potential realized savings from reductions in avoidable utilization and increased delivery efficiency.

- Development and Use of HGBs – the AHEAD Model will implement Medicare FFS and Medicaid HGBs, while encouraging increased commercial payer alignment. States will be required to develop a Medicaid HGB methodology, subject to CMS approval. These HGBs must be implemented in PY1, after the pre-implementation period.

- Reduction in Financial Risk for Participating Hospitals – CMS (i) will provide voluntary participation hospitals with upfront financial investments, (ii) has designed the Medicare FFS HGB methodology to incentivize early participation in the model, and (iii) may approve additional Medicaid flexibilities to reduce untended risk to participating hospitals.

- Complete and Quality Care Under HGBs – The purpose of state and hospital accountability for TCOC growth, quality, and population health outcomes under the AHEAD Model is meant to ensure patients benefit from enhanced quality and access (i.e., not reduced care). HGBs incentivize: (i) keeping patients healthy and out of the hospital, (ii) reducing complications during hospitalization, and (iii) better care coordination to prevent readmissions. HGBs will be adjusted over time to account for factors such as changes in the patient population, services provided, and performance in quality, health equity, TCOC, and other metrics.

- TCOC Accountability – the TCOC targets will be negotiated between CMS and each participating state (or state region) during the pre-implementation period. Hospitals voluntarily participating in Medicare FFS global budgets are accountable for Medicare FFS TCOC for patients residing in their service area through a performance adjustment to the global budget. Hospital accountability for TCOC performance will be phased in over the course of the model, starting with upside-only risk for participating hospitals.

- Primary Care Strategies – the AHEAD model incorporates lessons learned from existing state-based models and its framework will allow states to leverage existing state innovations while testing a suite of new interventions across all states. The AHEAD Model differs from previous models in three specific ways:

- It establishes a specific goal of increasing statewide primary care investment in proportion to the TCOC;

- It pairs HGBs with advanced primary care; and,

- It offers a flexible framework to implement advanced primary care alignment with the state’s existing Medicaid primary care program activities.

- Primary Care Practice Participation – primary care practices with an interest in participating in the AHEAD Model can consult with the applicable state agency eligible to apply. To be eligible for participation in Primary Care AHEAD, practices must participate simultaneously in the state Medicaid advanced primary care program or Primary Care Medical Home (PCMH).

- Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) Participation – FQHCs are eligible to participate in Primary Care AHEAD and will do so in the same way as non-safety net primary care practices.

- Benefits of Primary Care Participation – participating primary care practices will receive flexible, prospective, and enhanced payments which are meant to increase capacity for delivering advanced primary care services for attributed Medicare Part B patients.

- Required Criteria for Medicaid Primary Care APM or PCMH – each applicant’s Medicaid primary care APM or PCMH program should focus on enhanced care coordination services, including behavioral health integration and health-related social needs interventions.

Key Takeaways

CMS’ AHEAD Model, a TCOC model for states that will operate for 11 years, aims to achieve strategic goals that include improving population health, curtailing growth in healthcare costs, and furthering health equity. The AHEAD Model leverages existing state models and will be implemented via three cohorts, each with applicable requirements and time periods. While it requires certain infrastructure enhancements, the model provides upfront investments, resources, and tools to aid in success. Like other VBC models, the AHEAD Model aims to transition from traditional FFS payments to value-based payment structures with measurable results. These intended consequences include improved patient outcomes, lessened costs, and increased health equity. While the model includes planning and reporting requirements, incentives for participation and the opportunity to improve healthcare delivery are numerous.

The AHEAD Model represents a simultaneous effort across multiple states and extends beyond Medicare to encompass a multi-payer approach. This type of alignment across multiple payers represents a key component in promoting comprehensive, high-quality primary care across diverse patient populations and serves to manage costs, hospitalization rates, and aggregate patient outcomes. As applicable states begin to move through the pre-implementation process, additional investment and resources will be required.

Should you have any questions regarding the AHEAD Model or other VBC opportunities, please reach out to Principal Kelly Conroy at KConroy@AskPHC.com.

[1] As reported at https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/key-concepts/value-based-care.

[2] As reported at https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/key-concepts/total-cost-of-care-and-hospital-global-budgets.

[3] As reported at https://www.cms.gov/files/document/ahead-infographic.pdf

[4] As reported as https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/innovation-models/ahead.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] As reported at https://www.cms.gov/files/document/ahead-model-nofo-webinar-slides.pdf

[10] Ibid. CMS further notes that states participating in Making Care Primary (MCP) statewide may not participate in the AHEAD Model. If MCP operates only in a sub-state region of a state, the state may apply to participate in a different sub-state region, as long as there is no geographic overlap.

[11] As reported at https://www.cms.gov/files/document/ahead-model-nofo-webinar-slides.pdf

[12] As reported at https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/ahead/faqs.